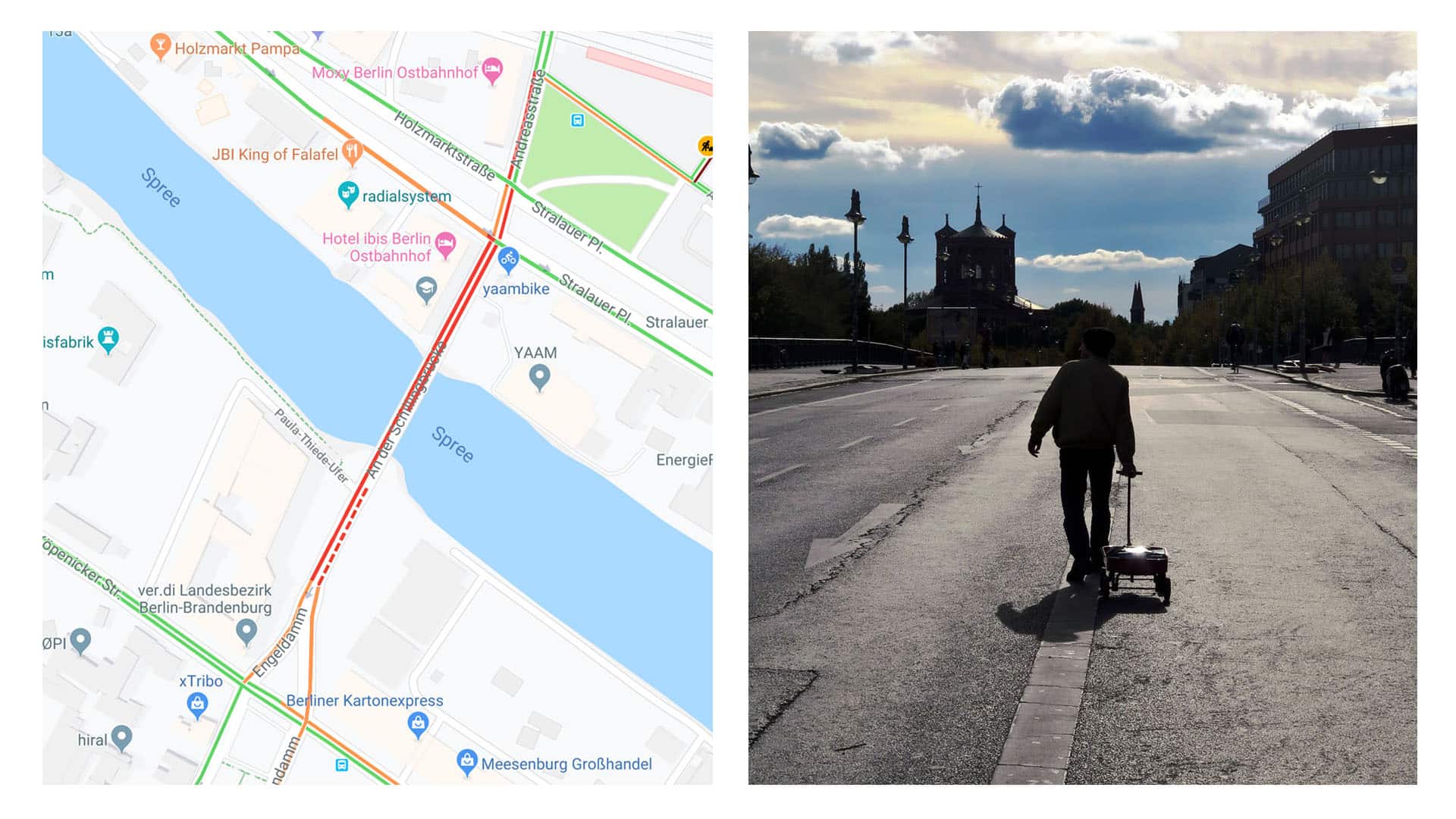

Leave it to an artist to pull off a simple Google Maps hack with nothing more than 99 smartphones in a red wagon on the streets of Berlin. It got us thinking about the implications of the impact of virtual reality (XR) on society. If 99 phones can alter a digital platform essential to our everyday lives, what will 99 people in VR be able to do? Or 99 avatars that are nothing more than digital entities with no connection to reality?

These are uncharted lands, somewhat like those early maps of exploration and conquest that left out half the boundaries of a continent. They simply didn’t know what was out there.

A Google Maps Hack With Smartphones

Simon Weckert got the idea for his Google Maps hack project from a May Day demonstration a few years back. The crowd of people resulted in Google showing a traffic jam on roads where there was none. It wasn’t cars, but everyone’s smartphones that triggered the dreaded red lines.

Time for a detour.

Armed with an idea, all Weckert had to do was borrow and rent 99 smartphones, get a red wagon, and walk around a few blocks in Berlin. It took an hour or so, but soon Google Maps was lit up with helpful warnings of traffic jams where Weckert had passed.

Of course, there was no traffic madness — just a creative artist pushing the boundaries of technology.

It’s a fascinating example of the way technology impacts society. And the way artists can unpack how technology shapes human behavior.

The Power of Technology

Simon Weckert quotes Moritz Ahlert’s article, The Power of Virtual Maps, in his description of the context for the project:

The advent of Google’s Geo Tools began in 2005 with Maps and Earth, followed by Street View in 2007. They have since become enormously more technologically advanced. Google’s virtual maps have little in common with classical analogue maps. The most significant difference is that Google’s maps are interactive – scrollable, searchable and zoomable. Google’s map service has fundamentally changed our understanding of what a map is, how we interact with maps, their technological limitations, and how they look aesthetically.

In this fashion, Google Maps makes virtual changes to the real city. Applications such as Airbnb and Carsharing have an immense impact on cities: on their housing market and mobility culture, for instance. There is also a major impact on how we find a romantic partner, thanks to dating platforms such as Tinder, and on our self-quantifying behaviour, thanks to the Nike jogging app. Or map-based food delivery-app like Deliveroo or Foodora. All of these apps function via interfaces with Google Maps and create new forms of digital capitalism and commodification . . .

The ultimate goal of Weckert’s Google Maps hack project is to understand how technology and specifically, Google Maps, shape human behavior.

. . . But what is the relationship between the art of enabling and techniques of supervision, control and regulation in Google’s maps? Do these maps function as dispositive nets that determine the behaviour, opinions and images of living beings, exercising power and controlling knowledge? Maps, which themselves are the product of a combination of states of knowledge and states of power, have an inscribed power dispositive. Google’s simulation-based map and world models determine the actuality and perception of physical spaces and the development of action models.

Google’s Response

With a ubiquitous platform essential to the DNA of so many tech start-ups and our everyday lives, Google had to respond to the faked traffic jam.

Traffic data in Google Maps is refreshed continuously thanks to information from a variety of sources, including aggregated anonymized data from people who have location services turned on and contributions from the Google Maps community. We appreciate seeing creative uses of Google Maps like this as it helps us make maps work better over time. (from Wired)

It’s about the same as saying we were blindsided. No doubt, Google will use this to improve its Maps platform before someone takes it a step further. But creative artists will find new ways to peel back the layers of the onion.

Determining Reality Through Technology

What’s so compelling in this project is that it’s not technically a “hack.” There was no breach of Firewalls and hidden code on servers; only a simple activity that impacted a platform essential to everyone in our increasingly digital society.

Here’s the artist’s short video of the project.

Wired quotes the artist.

What I’m really interested in generally is the connection between technology and society and the impact of technology, how it shapes us,” Weckert says. He cites philosopher Marshall McLuhan: We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us. “I have the feeling right now that technology is not adapting to us, it’s the other way around.

Of course, from a history of tech perspective, you could say there’s nothing new here. The railroads of the 19th century hardly adopted to the farmers they served and the people they transported – at least until the Interstate Commerce Commission was established in 1887 (becoming the first industry subject to federal regulation). And we still keep our phones linked to the time zones they created in 1883. Look up the “Day of Two Noons” if you’re not familiar with it.

Sometimes, you just have to stop time for the sake of technology.

Hacking Our VR Environments

It’s an unnerving thought if Simon Weckert (and Marshall McLuhan, to credit the source) is right. Even more so when it comes to VR. You might argue that there is nothing similar in the virtual arena. We have no platform with the long tentacles of Google Maps reaching into every corner of our lives. Nor do 99 VR headsets have the capacity to shape much of anything.

So far.

But we know the virtual can impact the real. And there’s a compelling possibility that VR can foster some degree of empathy, though that remains debatable.

The history here that goes back to the early days of the Web with the now classic, A Rape in Cyberspace. Virtual experiences shape our lives as our rudimentary social VR platforms have come to realize. Primitive as they are, they’ve have had to build in safeguards for people’s personal space.

No one knows where this virtual-real dynamic goes from here. Suffice it to say that our relationship to the virtual is far more complicated than putting on a headset. As Chris Milk aptly said of VR,

In the future, you will be the character. The story will happen to you.

The question is: who is writing this story?

Speaking of Simon Weckert’s Google Maps hack, Wired noted,

[The project] serves as a necessary reminder that the systems people take for granted involve inputs and outputs, and that they themselves are sometimes both. It shows how simple it is to fool a product in which people put tremendous amounts of faith. And it illustrates how maps aren’t neutral, either in their creation or their interpretation.

Are we ready to ask what people take for granted in AR, VR, and Mixed Reality? Immersive experiences are not merely neutral spaces we step into. They’re imbued with values, some obvious, others concealed. And they will impact our learning, the workplace, and ultimately, our lives in unanticipated ways. We see increasing concern about the hidden biases in AI. It will be no less of a problem in virtual reality.

And don’t get us started on the ethics of a brain-computer interface. Soon, we may not be hacking Google Maps so much as hacking into ourselves.

Present and Future

Right now, a large segment of the public is at the stage where virtual experiences fascinate through their novelty. Perhaps not much different than the Lumiere Brothers’ 50-second movie, L’arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat, with its train rushing toward the audience in 1896 (leading to one of the great urban legends in early cinema of people jumping out of their seats).

But as we take up residence in our newly created virtual worlds, we will need more than reactions of novelty and amazement. We will need skills to “read” virtual experiences. In truth, we need the skills to read the full-scale of human life rendered in VR. And we’ll need to understand how hidden biases shape human behavior, biases that are coded into our virtual environments.

Perhaps this is no different from the challenges of real life. But as always seems to be the case, the virtual world ups the stakes for what we fondly – and perhaps ever more quaintly – refer to as reality.

Emory Craig is a writer, speaker, and consultant specializing in virtual reality (VR) and artificial intelligence (AI) with a rich background in art, new media, and higher education. A sought-after speaker at international conferences, he shares his unique insights on innovation and collaborates with universities, nonprofits, businesses, and international organizations to develop transformative initiatives in XR, AI, and digital ethics. Passionate about harnessing the potential of cutting-edge technologies, he explores the ethical ramifications of blending the real with the virtual, sparking meaningful conversations about the future of human experience in an increasingly interconnected world.